With or Without the Sun

Chris Marker, the film-essay, and the meeting with Japan

9 March - 14 April 2018

Chris Marker, Chip Lord, Jorge Suárez-Quiñones Rivas, Magnus Bärtås, Noriaki Tsuchimoto, Takayuki Yoshida, Thorbjørn Bechmann, UMMMI, Wim Wenders, Yu Kaneko, w/ Fabian Hammerl, Jan Søndergaard

Programme organized by Staffan Boije af Gennäs and Christopher Sand-Iversen

Screening programme

The Koumiko Mystery and Level Five will be screened every Saturday from 13.00 during the exhibition period.

The exhibition With or Without the Sun explores, with Chris Marker’s seminal essay-film Sans Soleil as its reference point, the development and legacy of the essayistic tradition of filmmaking, both in the west and in Japan. The essay-film as developed by Marker and like-minded filmmakers such as Alain Resnais and Agnes Varda, is a genre that deliberately navigates in and expands the territory between fiction and documentary, overlaying the techniques of film and literary essay. While the camera records the world, the filmmaker’s voice probes the subject matter, reflecting on it and on him/herself without necessarily reaching a conclusion. This method has from the 1960s until today appealed to western filmmakers when approaching Japanese culture. The great influence of Sans Soleil as well as Marker’s lifelong interest in Japanese culture, have come to a certain extent to frame the approach of the essay-film when it turns its attention to Japan, but does not serve as the only definition of what has become a multifaceted genre. In its nature investigative and explorative, it has developed in a number of directions, for example The Eternal Virgin by Jorge Suárez-Quiñones Rivas uses images from the films of Ozu Yasujirō to interrogate the status of the images themselves.

In Japan, the tradition of documentary filmmaking may be divided into the ordinary (ke) and the extraordinary (hare). The ‘ordinary’ has often been labelled ‘diary film', or more recently ‘self-documentary’, terms which in fact cover a broad range of output, referring to work in which visual artists film and record facts in their personal environment. In this way it is related to the Japanese tradition of the I-novel, sharing its sense of disclosure, but is often also used to refer to films made after the Japanese release of Jonas Mekas’s 'Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania', in 1973. Another factor in the development of the Japanese tradition was the flood of news films during World War II, and the trend of “compilations” after the war, which took a new look at moving images from the past from a historical perspective. The ‘extraordinary’ was represented by filmmakers such as Noriaki Tsuchimoto, whose series of films about the Minamata pollution case made the problem known around the world, and is represented in the exhibition with On the Road, in which he turns his lens on the daily life of a taxi driver and his miserable and unhealthy working conditions.

In The Aroma of Enchantment, Chip Lord addresses the legacy of the American occupation of Japan following the end of WWII, revealing the extent to which the Japanese continue to idealize and live out aspects of the American 1950s, while unfolding how Japan was modernized through the introduction of technological developments and a constitution authored by the American General McArthur. In Tokyo-Ga, Wim Wenders inevitably encounters this modern Japan and its fascination with technology as he searches for any remains of the world represented in the films of Ozu Yasujirō, which repeatedly narrated the story of the dissolution of traditional family life as a metaphor for the decline of Japanese national identity following in the postwar era.

In the 1970s, Masato Hara attempted to make ‘The First Emperor’, a film about Japanese myths which, when he realized that the myths could not be found and were not filmable in a material sense, developed into a film about film and the myth of film: in the form of a projection of 16mm and 8mm footage to which Hara plays music and recites texts, this film performance can last from 6 to 8 hours. In A Man Who Became Cinema, Yu Kaneko traces the life of this ‘film poet’ through footage from Hara’s own films and Kaneko’s documentary recordings, charting the realities of Hara’s intense identification with life as a movie. It is also true to say that when taking Japan as their subject, the films of westerners often say as much about their own view of the world as they do about Japan, a tendency perhaps taken furthest by Marker, and most explicitly acknowledged by him: “To invent Japan is as good a way as any of getting to know it. … be there — dasein — and everything will be given to you into the bargain. A little, at least”, he writes in his photobook 'Le Dépays', an untranslatable play on words which may nevertheless be tentatively paraphrased as ‘The DisorieNation’.

While the films made by western artists and directors often make much of the visual and auditory noise and bustle of technological Japan, many Japanese filmmakers, such as Takayuki Yoshida, are still possessed of the restful and reflective character which, for Wenders, was exemplified by the oeuvre of Ozu. The photographs of Fabian Hammerl and Jan Søndergaard contribute just such a ‘quiet’ take on modern Japan, through the eyes of westerners.

In these ways the exhibition seeks to present not only a western interest in Japan, as exemplified by the essay-films of Chris Marker, but also to examine the ways in which the technological Japan we know today has been highly influenced by the socio-economic structures of the west, and how the Japanese, in various ways, understand themselves in relation to this new reality. In doing so their essayistic filmmaking posits a view of modern Japan which is by turns at odds and in concordance with the mode of address articulated in the western essay-film.

Works

Chris Marker, The Koumiko Mystery (1965). Marker meets the young woman Kumiko, and is attracted by the fact that she ‘isn’t an example of anything’, while ‘Japan is around her’ — she is a mystery, even to herself. Born Manchuria, China, educated in a French-Japanese school, she comments ‘I must be Japanese by now’. Their conversation in halting French, about politics, beauty, and the relationship of people to animals, is hindered by partial misunderstanding. After Marker’s return to Europe, Kumiko films and sends her answers to a list of his questions — the conversation continues across time and space, but distanced by the lens and tripping over language.

Sans Soleil (1983) is built up as a travelogue in which the main character travels between Japan, Guinea-Bissau, and Iceland. Letters supposedly sent by the cinematographer are read as a voice-over, reflecting on time and the nature of human memory, and the raid developments of life on earth. In a famous sequence, Marker uses images produced using some of the first image synthesizers, not in order to postulate a ‘modernity’, but to show that manipulated images were already a reality and would come to change our perception. In fact their author ‘Hayao Yamaneko’ is, like the cinematographer, a fictive figure. The film highlights the very personal nature of memory and its contingent relationship to experience, our often lacking ability to specify the contexts and nuances of our memories, and how this affects our perception of both personal and global history.

Level Five (1997). The heroine Laura is writing a video game to reconstruct the Battle of Okinawa, at the tail end of World War II. The Battle of Okinawa was dizzying in its loss of human life, but in the west today, hardly anyone knows it happened. The film includes interviews and vérité footage of the US Army’s invasion of the island, sandwiched between Laura’s monologues, a juxtaposition which suggests that shared histories are impossible to parse from subjective, lived experience. Laura has chatroom run-ins; survivors describe the violence they witnessed in unforgettable detail, including a first-hand account of the tragedy which explains how the Japanese army persuaded civilians it was better to die than to be taken prisoner by the Americans. To have the memory of the mass suicide preserved in the national consciousness is complicated. Memorials, for one, are always imperfect. Marker’s subject is both the conflict and our technologies for remembering it.

Chip Lord, The Aroma of Enchantment (1992), explores the fascination Japanese teenagers have for the American 1950s and 60s — they wear bobby socks, and Brylcreme in their hair. The film connects historical anecdotes about General Douglas McArthur with the director’s own feelings of alienation in the midst of Japanese culture. Lord focuses on stories told to the camera by Japanese collectors of American memorabilia and advocates of Americanisation. It is by turns humorous and mournful in its attempt to come to terms with questions of cultural displacement and western cultural influence in the 90s.

Jorge Suárez-Quiñones Rivas, The Eternal Virgin (2017) consists of clips from Ozu Yasujirō’s films in which the actress Hara Setsuko appears alone, indoors, including no visual, verbal or gestural interaction with another character, even one off-screen. The result is 71 shots from 6 different Ozu films. Setsuko is seen going about daily routines: walking down corridors, opening and closing doors, preparing and eating dinner. Rivas sees the film as a homage to the aesthetic power of banality, to the relation between time and space, the concepts of omote (public face) and ura (private face), and the porous boundaries between fiction and documentary. At the same time it visualizes a complex approach to Japanese culture, in that the Japanese filmmaker’s original representation of the female characters becomes a vision of the woman in the home, seen anew in the light of a (western) post-feminist gaze.

Magnus Bärtås, Kumiko, Johnnie Walker & The Cute (2006-07). The film is about Kumiko Muraoka, the main figure in Chris Marker’s The Koumiko Mystery, and Johnnie Walker, a Japanese homosexual Jew, who is seen by those around him as a foreigner even though his family have been Japanese citizens for generations. Choosing confrontation as his approach, and accompanied by his enormous Irish wolfhound, he challenges the Japanese ‘cuteness’ cult and its political meaning as a carrier of the neoliberal idea of Soft Power. Otherwise he holds readings in his home from a Haruki Murakami novel in which one of the characters is based on him. The director locates Kumiko Muraoka in Paris, and finds that she regrets her answer to question Marker asked 43 years previously, and writes and reads a new text instead. The real or fictive characters are reconstructed and placed in new relationships to their mixed, nomadic backgrounds.

Noriaki Tsuchimoto, On the Road (1963). Japan was in the midst of its long period of high economic growth and Tokyo was busy revamping its urban infrastructure. When most were celebrating the economic expansion, Noriaki Tsuchimoto focused his analytical gaze on the life of one taxi driver. What he saw were miserable and unhealthy working conditions, a Tokyo littered with traffic jams and construction work, a city where traffic accidents were multiplying and pedestrians unsafe. Coupling the tense visuals with impressive music, Tsuchimoto likens this supposedly new Tokyo to a skeletal wreck. On the Road was originally commissioned as a traffic safety film with the Metropolitan Police as one of the sponsors, but in reality Tsuchimoto was also working with the drivers’ union. When a police official finally saw the film, he dismissed it as “useless—the plaything of a cinephile", and so it was never used for its original purpose. While winning numerous awards abroad, including at Venice, it was shelved in Japan for nearly 40 years.

Takayuki Yoshida, Ponpoko Mountain (2016). This short film reflects on a quote by the artist Constantin Brancusi, ‘When we are no longer children, we are already dead’. All the images are taken at a ‘Ponpoko Mountain’, a kind of bouncy castle or trampoline shaped like snow-clad mountains, on which children play. Film and still images are mixed in meditative reflection on innocence and creativity.

Thorbjørn Bechmann, The Koumiko Project (2012). Taking Chris Marker’s The Koumiko Mystery as its point of departure, the film follows a young Japanese woman for some summer days and nights in Tokyo in 2012. She carries out actions and dialogue developed on the basis of Marker’s film. Camera and actor pass through several of the same areas that framed the original film. The Kuomiko project is the result of a fetishization of Chris Marker’s original film. The filmmaker’s obvious fascination with the portrayed woman is both a re-enactment of Marker’s fascination, and a realization by proxy of the filmmaker’s own — a fetishization on two levels.

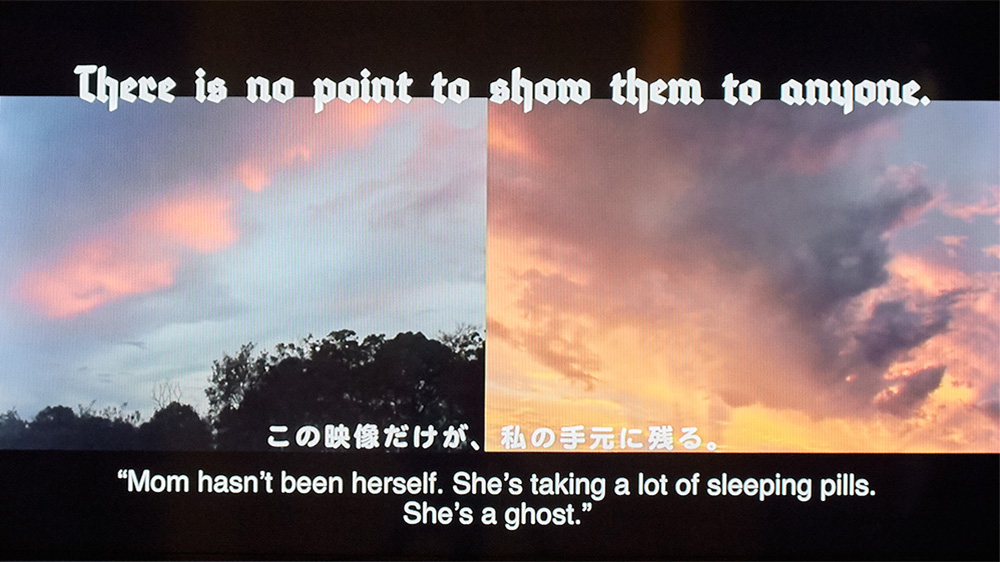

UMMMI, Pains of Forever (2015) represents a contemporary iteration of the ‘self-documentary’ tradition, in which she invites the viewer into the intimate realm of home video footage, only for the personal story told to end up questioning the meaning and relevance of these images. Probing the relationship between love and suicide, and hinging upon Goethe’s ‘The Sorrows of Young Werther’, the monologue speaks of the events that transpired between the narrator’s parents on their slow dance toward destruction. To cope is to quietly confront the ‘impossibility of communication’.

Wim Wenders, Tokyo-Ga (1985) is the record of a trip Wim Wenders made to Japan in the spring of 1983, seeking to learn whether anything remains of the world that Ozu chronicled in his 54 films, including Tokyo Story, which is seen by many as Ozu's masterpiece. Wim Wenders describes how Ozu gave us a vision of the decline of the Japanese family and, with it, the decline of a national identity. When Wenders visits Tokyo for the first time, he finds a very different city, one with a booming fascination with technology that often clashes with the traditional elements of Japanese culture. In the film Wenders also talks to Ozu's cinematographer, Yuharu Atsuta, and Chishu Ryu, an actor who frequently collaborated with Ozu.

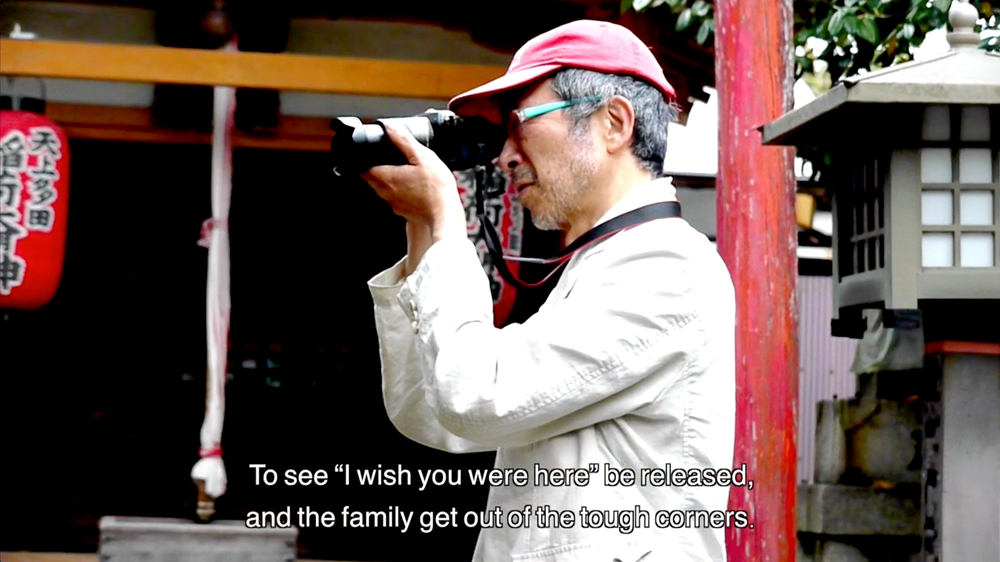

Yu Kaneko, A Man Who Became Cinema (2018). Kaneko interviews the filmmaker Masato Hara as he talks about his entry into filmmaking, and follows him in his everyday life as he tries to make ends meet and complete a new film. Juxtaposed with this we see footage from Hara’s earlier films, which makes it clear how closely his work is related to his life: both in the images he shoots and in the way he presents his films, accompanying them with music and narration, the apogee of which is The First Emperor, a performance that is different every time. Interviews with others underline how Hara’s passion for filming makes it seem as though he sees his life, and perhaps even himself, as a movie. The film charts Hara’s struggle with everyday life, and at the same time Kaneko’s own struggle to become a filmmaker.

Fabian Hammerl’s photos often arise when walking through an environment, which for Hammerl is both a question of taking a stroll and an act of defiance and protest. It is both a pleasurable activity and a method of critique: he wanders the streets both as a 21st century flaneur, enjoying chance encounters with unexpected sights, and as a 21st century ‘dériver’, taking unplanned routes and encountering multifarious uses of urban and suburban space, intent on overcoming the intended ways of moving through the surrounding environments. His records of these walks arise through careful framing and composition of the subject.

Jan Søndergaard exhibits a selection of photos from his book Tokyo 123, which tells three stories: the first about the black crows of Tokyo – that are slowly, park by park taking over territories from humans — and the attempts to control them; the second about the thin line between urban living and the close and neighbourly relationship it has with with a nature worship deeply embedded in Japanese culture and religion; the third about very small variations in Japanese everyday aesthetics, which, caught in his outsider’s gaze, are crystallized into rare, slightly alien entities.

Staffan Boije af Gennäs has been working as an art critic since 1993. He writes text for books and catalogues for artists, photographers, theatre groups and dance companies. In 1994 he started curating exhibitions, initially in cooperation with Galleri Struts in Oslo. In 1995 he co-founded Galleri Rhizom in Århus, Denmark. A selection of exhibitions he has curated includes:

Blondinen som forsvandt, Bechmann’s, Copenhagen 1997

Loving at Home, Center for Analysis & Research, London 1999

Ingrepp, Uppsala Kunstmuseum, Uppsala, Sweden 2002

“The Post Group Show Dilemma”, parallel event to the 9th Biennal of Art of Istanbul, Turkey 2005

I need no map, Anna Akhmatova Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia 2007

Nordic Darkness, Kristinehamns konstmuseum, Kristinehamn, Sweden 2011

Christopher Sand-Iversen is a founder member of SixtyEight Art Institute and also the founder and editor together with artist Hugo Hopping of SixtyEight's publication arm, Really Simple Syndication.

With or Without the Sun is being held in association with CPH:DOX.

The organizers would like to thank the following people for their generous help and advice: Jasper Sharp, Joss Winn, Mads Mikkelsen at CPH:DOX, Takayuki Yoshida, Yano Kazuyuki at YIDFF, and Yu Kaneko

Every attempt had been made to trace the copyright holders of The Koumiko Mystery (Le Mystere Koumiko), without success. We have therefore restricted the screening of The Koumiko Mystery to 5 Saturdays. Any breaches of copyright this may have led to are involuntary and unintended. Rightful claims will be met on the same terms as if prior permission had been obtained.